Alexander Digs into French Cemetery Data to Explore Life, Death, and Ephemeral Rest

For art historians, cemeteries serve as one of the most important ways to not only study the art of a period, but also learn more about the culture, the people, and the customs of a time. The grander and larger tombs of famous individuals, however, often command the most attention from scholars.

Originally published by The Graduate School.

For art historians, cemeteries serve as one of the most important ways to not only study the art of a period, but also learn more about the culture, the people, and the customs of a time. The grander and larger tombs of famous individuals, however, often command the most attention from scholars.

With the most eye-catching monuments hoarding the scholarly spotlight, Kaylee Alexander took a different approach and set her sights on the invisible.

“We save the graves of the important people and just let everything else fall by the wayside,” she said. “So what I really wanted to ask was what did all these other tombs look like? Who did they belong to?”

Alexander, a Ph.D. candidate in Art, Art History and Visual Studies, comes from a background in art history, having completed her master’s research within the discipline. She began her Ph.D. research studying 19th-century landscape painting, but her path completely changed after a trip to the Catacombs in Paris.

“My advisor at Duke encouraged me to look more into cemetery sculpture,” said Alexander. “The more I learned about the regulations and temporary burial system in France, though, the more I got frustrated with cemetery sculpture and moved to popular commemoration.”

Her recently defended dissertation, titled “In Perpetuity: Funerary Monuments, Consumerism and Social Reform in Paris (1804–1924),” uses a data-driven approach to study Napoleonic reforms in burial customs and commemoration, helping us to see cemeteries in a new light.

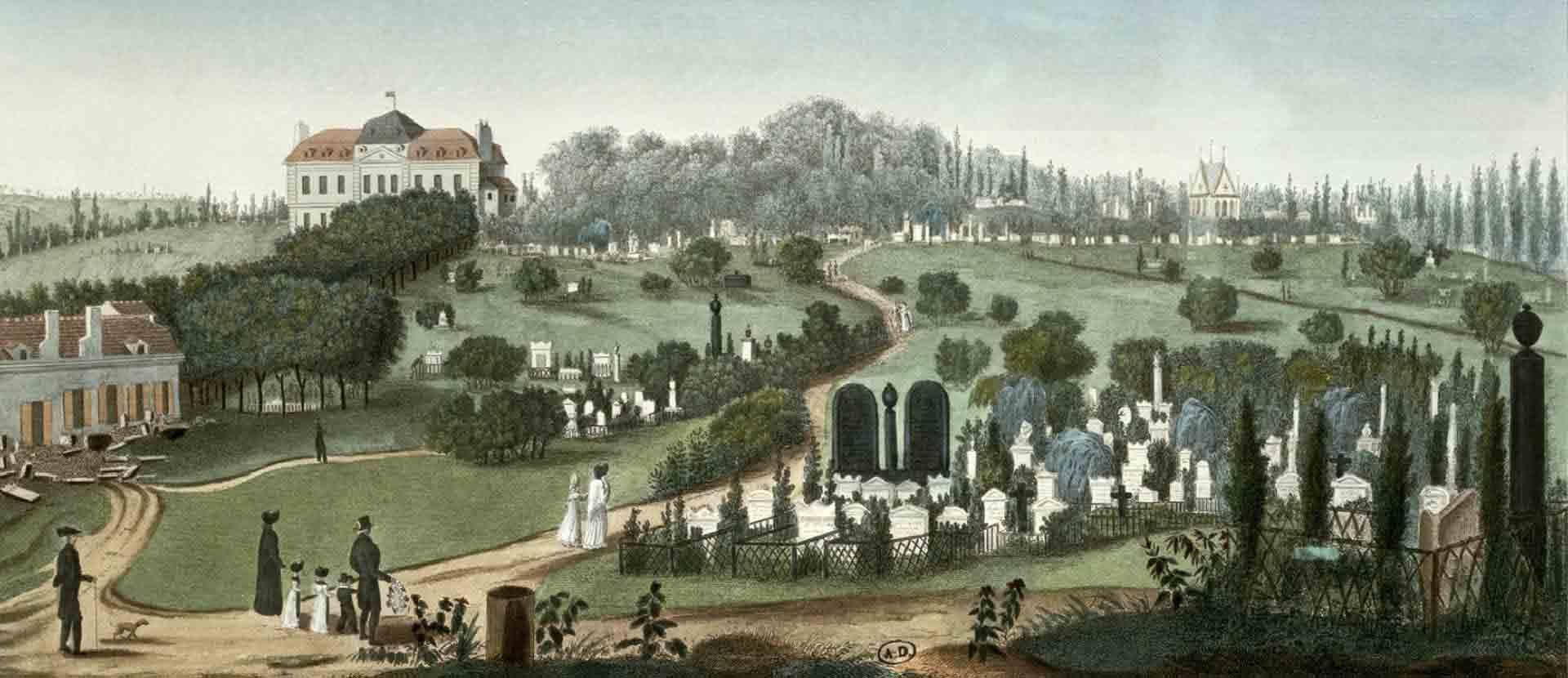

In the early 19th century, Napoleon instituted a new system of burial traditions throughout France that ensured, for the first time, that everyone in the empire would have access to their own burial plots. This was a completely new way of burial, but there was a catch: The burial would only be guaranteed for five years, unless the individual or family had the money to pay for more time.

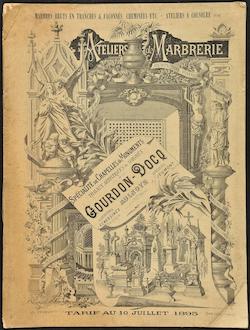

funerary monuments (image courtesy of

Kaylee Alexander)

This led to the disappearance of the graves of those who couldn’t afford more than the guaranteed five years (see video below). In her dissertation, Alexander used data from the time period to understand what these tombs looked like and to whom they belonged in order to better understand the people of the time.

“I was really interested in seeing what a data-driven approach to this material could bring to the table—what aggregates of information tell us about general trends in this period?” said Alexander. “How could these other sources help us to get a better idea of what monuments were like, even if we don’t have any surviving material evidence? Can data-driven work help us to study stuff that no longer survives?”

During her time in The Graduate School, Alexander has taken full advantage of research groups, fellowships, and other opportunities to support her work. She has received the International Dissertation Travel Award, the James B. Duke International Research Travel Fellowship, and the Eleonore Jantz Reference Intern Fellowship with the Rubenstein Library. Her work has also been supported by five summer research fellowships.

Alexander has also found assistance from her mentors during her research process. For instance, her primary advisor, Neil McWilliam, not only helped her with data analysis and methodology, but also “has been really great at balancing between letting me prove to him why what I am working on makes sense—and how I am doing it will work—and pushing me when things are unclear,” she said.

“When I started at Duke, it felt like my advisor was always skeptical of what I was saying and doubting what I was working on, but eventually I learned that I just needed to find more evidence or make myself clearer in what I was saying. Don’t give up on a weird idea, pursue it if it’s something you’re sure of, and then prove it to your advisors.”

Video: Perpetual vs. Temporary Burials

A data visualization of the ratio of perpetual and temporary burials in Père-Lachaise Cemetery in the 19th century.