Made Possible by Reggie

It was late spring and a procession of eager undergraduates and their families had gathered in Wallace Wade Stadium waiting for the commencement of the Class of 1978 to begin. Moments later, the students would walk across the stage to their futures. But for now, they were filled with wonder.

Many wondered about the future just ahead. Some would go on to law school or medical school. Others would start their own businesses or run for office. They would become pillars of communities, build houses and start families. They would give of themselves to help others. They would shape and make a better world.

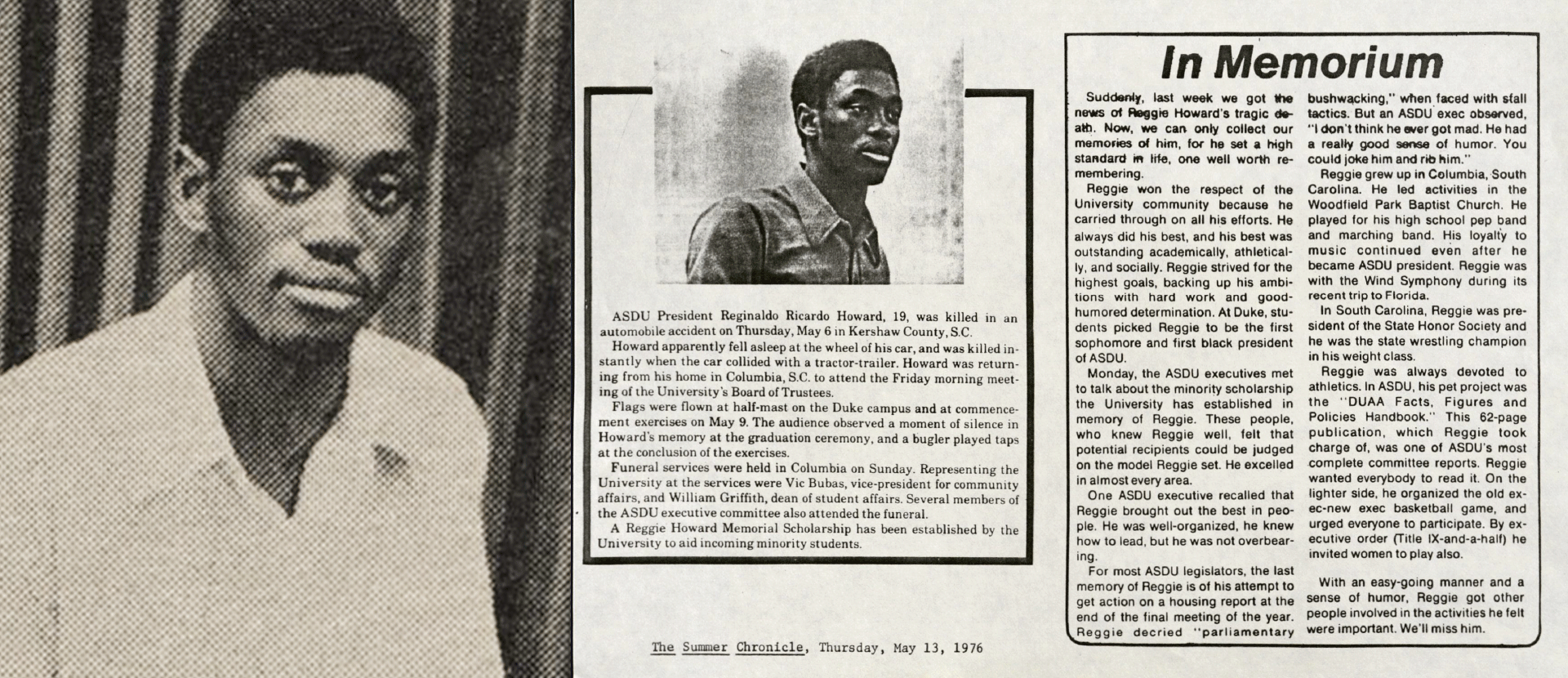

Some wondered about the past, too. They let their minds return to the spring of 1976, when they were just students with homework and residence hall friendships — still two years from graduation. They remembered the face of their friend and classmate Reginaldo “Reggie” Ricardo Howard, and they wondered what Reggie would do with his life if he could triumphantly walk across the stage and graduate with them.

They wondered because Reggie was the definition of unlimited potential. Reggie was unforgettable.

The Promise of Reggie

In 1974, Reginaldo Howard attended Duke on an Angier B. Duke Scholarship, a merit-based memorial scholarship and one of the university’s highest honors. He was from Columbia, South Carolina, but his parents, Eldeka and William Howard, were from Panama. He had a brother, William Jr., and a sister, Tanya. Reggie also had big dreams. His clearly articulated talents brought him from Spring Valley High School to Duke to study political science and public policy.

On campus, his affability was effusive. He knew nearly every undergraduate student and took part in many activities, including the marching band, Black Student Alliance and Baptist Student Union. Even as a freshman, he had an immediate impact. It wasn’t long before the realization of his skills, intellect and diplomacy got him elected president of the Associated Students of Duke University (ASDU), which was then the student body government, for the 1976-77 academic year.

Bear in mind, Reggie won as a sophomore and as a person of color. It was a first in both instances. This was less than a decade removed from the Allen Building Takeover — and fewer than 15 years after the first Black students matriculated at Duke.

Upon word of his election, many from his community in Columbia wrote letters of congratulations to Reggie and his family for his momentous achievement, including Sen. Ernest F. Hollings (D-S.C.); Rev. Gary A. Smoak from Woodfield Park Baptist Church, Reggie’s hometown congregation; and Keith E. Davis ’58, Ph.D.’63, provost at the University of South Carolina. Then, almost as quickly as he arrived, Reggie was gone.

On May 6, 1976, only a few months after his election, Reggie was returning to Durham to attend a Board of Trustees meeting when he was killed in a car accident in Kershaw County, South Carolina. In his passing, Duke wasn’t just deeply hurt, it was galvanized.

The community that loved him most wouldn’t allow the tragedy to be the last the world would hear from Reginaldo Howard. But it first had to determine the most enduring way to memorialize someone so young and gifted.

In the two years that Reggie spent at Duke, he blazed trails. His campaign materials, now housed in the Duke University Archives, show that Reggie was deeply committed to working with those around him, including students, faculty and administration, to make the university better.

Better to Reggie meant lighting the way and making things easier for those who would come next. He ran on a platform including causes such as student housing, the arts, Black studies and university budget priorities which affected students. As president-elect, he wanted to literally light parts of the campus as well. He petitioned to have segments of outdoor lighting on campus upgraded to improve campus safety. The first portion of upgrades was completed, before he had officially taken office, in the main quadrangle outside of Duke Chapel.

Reggie corresponded with William J. Griffith ’50, dean of student affairs and assistant provost at the time, to find money in the budget to keep the Duke Libraries open 24 hours a day during the week of exams. And, very democratically, Reggie held open interviews for positions within his cabinet and hosted a working retreat to share his vision. People saw what Reggie saw because of Reggie. They believed.

In a letter dated March 16, 1976, Reggie wrote to a list of confidants at Duke about his presidency:

“As your newly-elected Associated Students of Duke University President, I am sincerely looking forward to and gratified of having the opportunity of serving you and my fellow students to the upmost of my capacity for the coming year.

“Hopefully, working together in unison, we will be able to fulfill some, if not all, of our goals that we are striving to attain for the betterment of Duke University.

“My office is always open, so please feel welcome to call on me for assistance at any time.”

Finally, the community determined the best way to remember him.

Reggie was deeply committed to working with those around him, including students, faculty and administration, to make the university better.

As early as his wake, members of his family, the ASDU cabinet and others in the Duke community, such as Caroline Lattimore Ph.D.’78, worked quickly to secure a memorial scholarship in Reggie’s honor. By May 25, 1976, the Board of Trustees had unanimously approved the Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholarship, and Duke President Terry Sanford created the fund. It offered up to 10 students $1,000 of funding per year for four years, supported by the university’s general operating funds.

The scholarship selected students on the basis of merit and not financial need. In the mid-’70s, this covered roughly 33% of Duke’s cost of tuition. From there, the scholarship program continued to grow.

A Perpetual Source of Support

For early Reggie Scholars like Dr. Larry Johnson ’81, who is now a member of the Trinity Board of Visitors, Duke in the context of Reggie is what attracted him to attend. Johnson was initially offered a chance to compete for an A.B. Duke Scholarship, but he had to work a part-time job at Sears the weekend of his invitation. It seemed he had missed his chance, but then he received a second letter offering the Reggie Scholarship.

Soon after, Johnson took a day trip from Maryland with his father to tour campus. He was struck by the chapel and gardens, but ultimately the conversations he had during his first visit made him a Blue Devil.

“I met a couple of African American students who saw my dad and me walking around West Campus and approached us. They talked to us, and sat down, and took the time to explore what Duke was all about,” says Johnson.

“At the end of the trip, I said, ‘This is the place. This is where I want to go.’”

Many of the first Reggie Scholars to come to Duke didn’t know which other students might also be recipients of the prestigious award. Even though it brought exceptional students to campus, the scholarship wasn’t yet broadly recognized as being equivalent to other merit scholarship programs. And some scholars, particularly those from underrepresented groups, were reticent to discuss financial awards openly with their peers. For people of color, the social climate at large was even less inclusive. Some Black students were questioned, “How did you get here?” as if they didn’t belong. Moreover, there wasn’t yet a formal structure devised by the university for the program and its scholars. They received academic advising along with financial support, but the program needed more time to cultivate and mature. In short, it needed more of Reggie.

The scholarship was also up against the clock. The university required that any new scholarship reach a minimum principal of $25,000 in order to be endowed. Without endowment status, the university approved its funding for only 10 years. With the future of the scholarship in jeopardy and time running out, the students drove what happened next.

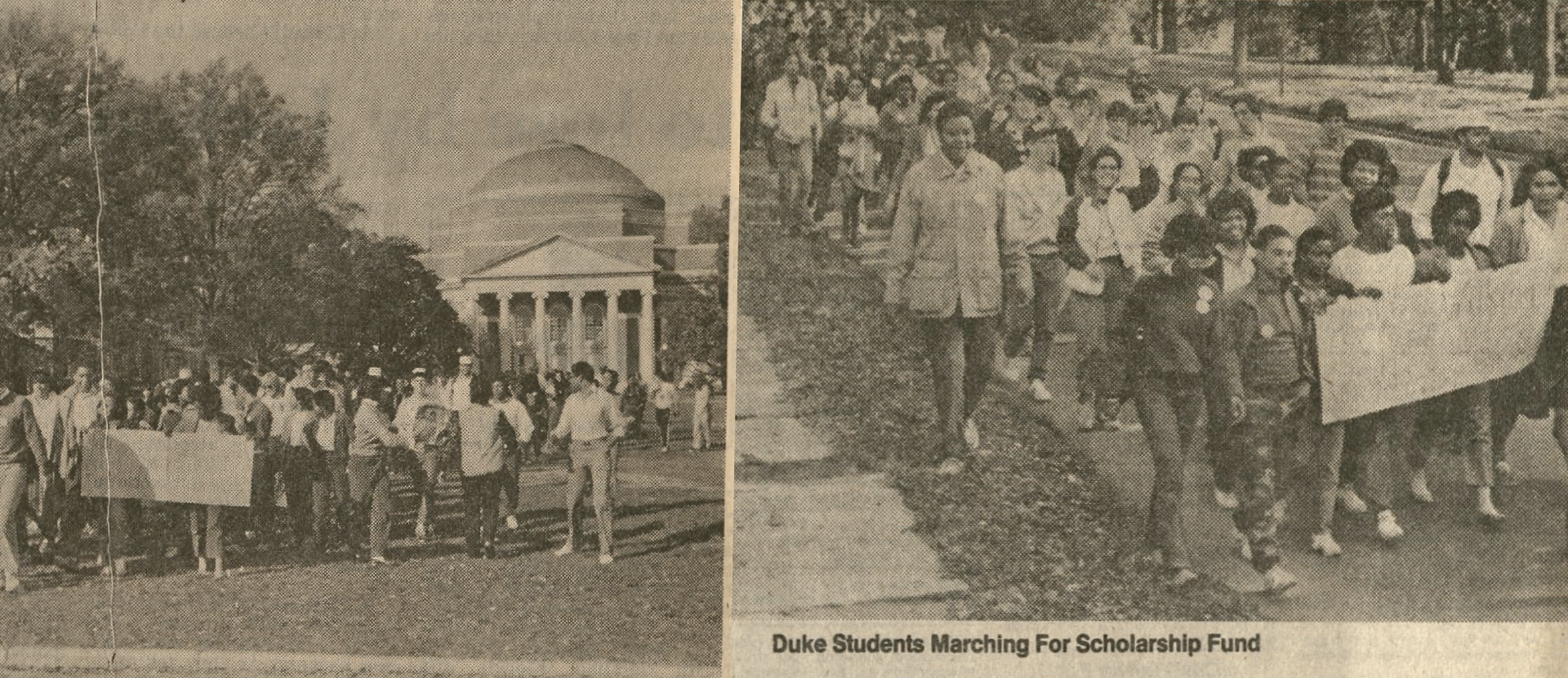

Over 400 students, faculty and advocates of institutional equity marched on East and West Campuses to raise awareness and build support for the scholarship like Reggie would have done. The march raised more than $4,000, garnering gifts from current students, Black alumni and businesses, such as North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Co., and many others. At a time when A.B. Duke Scholars were granted full tuition to attend, student activists were seeing to it that Reggie Scholars receive equitable financial aid awards for their academic merits.

In the same year the march took place, Duke launched a $200 million fundraising effort called the Capital Campaign for the Arts and Sciences. In 1984, under 30% of Duke students received merit and need-based financial aid. By comparison, 52% of today's undergraduates receive some form of aid. The importance of securing investments to relieve families of the financial burden of the cost to attend, especially for students from underrepresented groups, was evident.

Now the Duke community and the will of the institution were in full alignment. They agreed that finding philanthropic funding for merit scholarships like the Reggie Scholars was a top priority. In 1989, Duke received an anonymous $500,000 grant. The university matched the grant’s funds over the next five years, helping to transform the Reggie Scholars program into what it is today: nearly a half-century of deeply layered impact on scholarship and leadership.

At Duke, Reginaldo Howard’s leadership and vision have become emblematic of what it means to embrace the academy as a family. It is why Johnson, who has had a successful career in medicine and then in the pharmaceutical-biotech industry, and others like him have continued to support the program over the years through philanthropy. “We have to make sure that each generation has the opportunity to step higher,” Johnson says.

“I want to give other young people the opportunity at Duke that I had. And, to see that these students are able to go through school without that financial concern and that they have people mentoring them, it warms my heart. It’s very special,” says Johnson.

For some Reggie Scholars, the enduring commitment from the university and donors to endow the program meant they could attend. The scholarship now covers the full cost of tuition. One example is Michael Ivory Jr. ’18, who says he came to Duke from a low-resource background. He saw being a Reggie as an incredible opportunity to give back and to uplift people in communities like the one he’s from in Miami. He sees the Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholarship in the context of something bigger.

“Reggie was made possible by someone. In turn, we are made possible by Reggie,” Ivory says.

“You can talk about Reggie. You can talk about John Hope Franklin Hon.’98, or Samuel DuBois Cook Hon.’79. You can talk about Dr. Brenda Armstrong ’70. These people are stars within a constellation. They light the path for us.”

We have to make sure that each generation has the opportunity to step higher.

– Dr. Larry Johnson ’81

Together, these and other Duke luminaries, and other people of color within the broader communities which Duke students and alumni find themselves apart of, make up a map of generations of stars that glimmer with growing intensity. The map casts an indelible light across the university and beyond it for any young person in the future to look up to and use to find the way to their ambitions.

Meet Today’s Reggie Scholars

Today, being a Reggie Scholar means being part of a family. The impact of this family sets it clearly apart from other merit scholarships. To Duke, it brings roughly 20 to 25 students of astounding merit who emulate the life and values of Reginaldo Howard. For the scholars, the program provides financial support — covering the full cost to attend and additional funds for domestic and international summer experiences — and an academic community and enrichment opportunities. The newest program director is Valerie Ashby, dean of the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, and one of Duke’s most respected and effective leaders. Reggie’s legacy and what it means for students from underrepresented groups at Duke have meant Dean Ashby is remarkably dedicated. She meets regularly with each of the scholars and draws out the leadership they hold within themselves, which has made their journeys at Duke more meaningful and successful.

“It’s a privilege to be part of these outstanding students’ educational experience and to help ensure they maximize their time at Duke. I continue to be amazed by the intellect, leadership and humility exuded by our Reggies. And there’s no more joyful part of my job than seeing a Reggie — or any student — reach their full potential,” says Ashby.

Julie Williams ’19 spent her time as a Reggie Scholar diligently pursuing connections around the globe to flesh out her interests in public policy and ethics. She’s worked closely with Syrian and Iraqi refugees as part of Duke Immerse in Amman, Jordan, and with MASTERY Refugee Tutoring in Durham at the Kenan Institute for Ethics. While at Duke, she was selected to intern at the Obama Foundation, where she worked with their international team on the Foundation Leaders: Africa Program.

“My mom volunteered for the Obama campaign in 2008. And I helped make calls for it when I was little, in the sixth grade. To go from that, to now working for the Obama Foundation, was surreal.”

Connecting it back to Reggie, Williams adds: “Having opportunities like that make you really appreciate being at Duke and being a Reggie — and all of the things that Reggie did as a person to get you there.”

After graduation, Williams moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to take a gap year to pursue her talent as a singer. At Duke, she was an artist for Small Town Records, Duke’s student-run record label.

“Knowing that you are not paying for your time at Duke, it takes a lot of pressure off of you and it gives you the ability to be able to explore. That’s one of the things the Reggie program does.”

For junior Eric Little, he chose coming to Duke over other opportunities on the table like the prestigious Morehead-Cain Scholarship at the University of North Carolina, and Ivy League offers at Princeton and Penn, because of the lineage of Reggie.

“One of my biggest mentors that I’ve had in my entire life is Sinclair Toffa ’18. He works at Palantir Technologies in London.” Little says the two of them met up in Puerto Rico last year because they both happened to be traveling there during spring break.

“I still text him when I need anything. He was a Reggie and one of the biggest reasons I came to Duke.”

The familial network Little has experienced since arriving in the scholarship program is something he’s proud to build upon. One of the ways he does so is by being an advocate for the Community Empowerment Fund. With CEF, Little has helped residents in Durham and Chapel Hill write resumes, budget their finances and even find housing. In addition, Little has interned at McKinsey & Company and Deloitte, honing his aspirations to build a career in finance or consulting. And, as a project leader, he spends Monday and Thursday evenings working with ninth through 12th graders at Hillside High School in Durham on a Duke Innovation & Entrepreneurship start-up incubator program for teens called Audacity Labs.

Giving back as a mentor and sponsor is a tenet that rings true for all Reggies. For junior Katlyn Hurst, it is deeply embedded in the outcomes she seeks for others. As the oldest of seven siblings, Hurst often fell into the role of a tutor growing up. Coming from Memphis, Tennessee, she says she attended schools in low-resource communities that lacked opportunities. Once she found more support, she started giving back. In high school, she mentored girls coming from underprivileged communities so they could experience dance at the Bing Dance House through Eikon Ministries in the Binghampton neighborhood of Memphis. Now at Duke, each summer Hurst has worked with the Imani Foundation. She has become a champion for the foundation’s mission: to encourage youth to look beyond their boundaries and to help them begin a journey of self-discovery to make their dreams possible.

“Every student has the potential to be incredibly smart — they just need people who can push them. We need to make sure everyone has as many opportunities as they can to do something incredible.”

Hurst is pre-med, majoring in biology and minoring in education. But even as a Reggie, she found it difficult to become involved in a research lab because spots are so competitive. For several weeks, she wrote to lab managers but received no response. When Hurst continued to be unable to find a research opportunity, she decided to text Dean Ashby.

The response she got surprised her. Dean Ashby texted her back and soon introduced her to Gary Bennett, Duke’s vice provost for undergraduate education.

“Regarding my various passions, Dean Ashby told me not to limit myself to one subject, major or research lab. She is the only person who has made me dream bigger than I already had,” says Hurst.

Bennett then connected her to another research professor. Through this collective effort, Hurst found a team with the Motivated Cognition & Aging Brain Lab and has published research.

Kendall Bell ’19 came to Duke from close-by Cary, North Carolina. He says he probably wouldn’t have attended if it wasn’t for the scholarship. But what he found on his first day as a Reggie was unsettling.

He and other high-school hopefuls invited as finalists to compete for the four or five scholarship spots that year arrived on campus the same day a heinous and hateful act was committed: a noose was hung from a tree. But from those hurtful moments, Bell says that no one steered away from the realities of what happened.

“For a scholarship focused on students of African descent, it was a good thing to not pretend this wasn’t happening.”

Immediately, the group broke from their schedule and circled around one another to have a conversation. Administrators and faculty asked the scholars how they were feeling and what they were thinking. The Reggie Scholars then attended a rally outside of Duke Chapel. They kept talking about it.

“They confronted it head on,” Bell says. “They said, ‘This is what it’s like to go to a university like Duke sometimes.’”

He felt genuinely cared for and ultimately the courage he saw that day made him a Reggie. Bell finished his studies as a chemistry and cultural studies double major, with a minor in African and African American studies. Now a Duke alumnus, he wants to teach in rural North Carolina to give every student the opportunity to think critically, ask tough questions and be an active participant in learning.

“When you talk about carrying on the legacy of Reggie, it doesn’t mean you have to be Reggie,” says Bell. “Reggie had ideas to transform campus and bring people together, and he talked about that explicitly. That’s creating a mission and creating community.”

To Bell, Reginaldo Howard’s legacy lives on through what each of the scholars does with their lives and the unique paths they blaze.

“The world now is a different place than it was then. But that doesn’t mean we can’t still consider how we can bring people together.”

It’s tough to speculate what Reggie would have done, and where his trailblazing would have taken him, had the world not lost him.

Some might suggest looking to those who share the similar skill set of a trailblazer with Reggie, such as Frank Emory Jr. ’79, the first African American student body president at Duke who served, and what Emory has done as an accomplished attorney, resolute leader, and mover and shaker. Emory now serves on Duke’s Board of Trustees and Executive Committee. He continues to shape the future of the university.

Had he walked across the stage, Reggie might have improved American life, and made a difference in how we lead and lean on one another.

He is doing so right now with his family of scholars.