Rising Tides: Meet Orrin Pilkey Fellow Sarah Lipuma

Everyone from the Jersey Shore remembers the storm. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy barreled through the Mid-Atlantic region with conditions ripe for destruction.

The storm brought wind and rain with sound and fury. It made landfall in Brigantine, New Jersey, just north of Atlantic City, where it left several million residents without power, inundated communities with flooding and storm surge, and caused the state upwards of $30 billion in damage.

People dotted along the water in coastal communities live with the consequences of storms like Sandy. One of the things often overlooked in the conversation is that people most affected by these storms tend to come from lower resource backgrounds, making them more susceptible to the economic hardships that ensue from the storms’ lashings. It can take years for families to financially recover.

Still, those who live on the coast know the next big storm is always on the horizon, ready to take the landscape around them and everything they love away with the tides.

The New, New Jersey Shore

After working for several years at environmental nonprofits, Sarah Lipuma was ready to do more. She began looking into graduate school to further her career, but Duke had never crossed her mind.

“I’m from New Jersey, so I was looking at schools in the Northeast,” says Sarah. “That’s when I saw how unique and interdisciplinary the Nicholas School of the Environment is.”

Sarah did not want to go down an academic track to teaching or hard-coded research afterward. What she aspired to do was a little more community based, working with people hand in hand to prepare for climate problems. Things seemed to be getting worse.

“I wanted to get out in the field as soon as I graduated to start working, helping communities prepare for hurricanes,” Sarah says.

Sarah applied to Duke for its collaborative approach to science, much of it focused on solving real-world problems right now. But even after being admitted, Sarah’s attendance to Duke wasn’t a given due to the financial requirements.

Then she was offered the Orrin Pilkey fellowship, opening a pathway to funding she would otherwise not have available.

“Many of the conversations happening now are a direct result of Pilkey’s work,” Sarah says. “He paved the way. I was extremely inspired by him.”

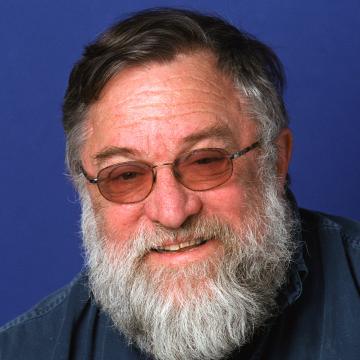

Orrin H. Pilkey, James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Geology at Duke University, is the godfather of coastal geology and beach conservation. From researching the abyssal plains of the ocean floor to human impacts on beaches the world over, for half a century Pilkey has been making headway in the field in hopes of better understanding humanity’s future at the edges of the oceans.

Research That Matters and Tells a Story

Now holding the fellowship which honors her academic hero, Sarah is a Master of Environmental Management candidate at the Nicholas School of the Environment. She is learning about coastal environmental management to take better care of the coasts and the people who live there.

One particularly interesting aspect of Sarah’s research examines the intersection of social equity and climate change. This seems especially important given that so many impacted by storms also live paycheck to paycheck. Doubly so as tourism and fishing are transformed by the effects of climate change.

As a graduate student, Sarah started investigating the places she knew best: the ocean, marshes and wetlands of her home state. In thinking about the Garden State, her hometown in Ocean County, New Jersey, and Hurricane Sandy, Sarah wondered if it would be wise to rebuild everything exactly as it had been before the storm came through.

Residents of New Jersey will tell you about Sandy’s destruction — many are still recovering from it. One of the most visually arresting moments of the storm occurred when it crumpled the Star Jet steel roller coaster, owned and operated by a casino, and swept it into the ocean.

The visual was like the finale of “Planet of the Apes,” where man must reckon with his hubris. Except this time for tempting the water’s edge. In 2017, a replacement coaster named Hydrus was built.

“I looked at it as if we hadn’t learned many lessons,” Sarah says. “We wanted to get back to being the fun Jersey Shore.”

Being steeped in the academic community and knowledge in the service of society that the Nicholas School provides, Sarah began to wonder if there were other pathways forward for her community back home. Instead of returning to business as usual, she decided what they needed was long-term planning imbued with an outlook to adapt.

Sarah started looking to other disciplines to further inform her climate research, which is part of what attracted her to Duke. Moving across disciplines is not something that can be taken for granted, but at Duke it happens every day. In her studies, Sarah has learned and benefitted directly from scholars in policy and law, as well as urban planning and statistics.

In terms of social equity, one thing Sarah has discovered is that ownership of land and property rights along the coast often have impacts in unforeseen ways.

One of the things he shared with me is that if you can see the sea, the sea can see you.

-- Sarah Lipuma

Sarah started looking to other disciplines to further inform her climate research, which is part of what attracted her to Duke. Moving across disciplines is not something that can be taken for granted, but at Duke it happens every day. In her studies, Sarah has learned and benefitted directly from scholars in policy and law, as well as urban planning and statistics.

In terms of social equity, one thing Sarah has discovered is that ownership of land and property rights along the coast often have impacts in unforeseen ways.

Despite an increasing frequency of storms and the dangers of flooding documented by science, the development of the American shoreline has been at a near constant since the 1950s. Originally consisting of only small, temporary fishing villages, America’s coast has been built up over time as a place to vacation — and escape.

Now, climate change has caught up and is threatening this way of life.

The Nicholas Annual Fund Does It All

Even though Sarah has not taken any coursework with Pilkey, as he’s retired from teaching, Sarah did meet the distinguished professor at Duke’s annual Scholarship and Fellowship Dinner.

Every year, this private event connects talented young scholars at Duke with many of the donors who have helped make their education possible. At the dinner, Sarah’s mentor inspired her even more.

“One of the things he shared with me is that if you can see the sea, the sea can see you,” she says. “I love that.”

Pilkey turned out to be just as personable in person as he comes across in his ground-breaking research. And since their chance meeting, Sarah has maintained a rewarding connection with him.

She’s grateful every day that her work has been made possible in part by unrestricted gifts of financial aid to the Nicholas School Annual Fund.

In fact, these flexible resources provide many of the tools environmental scholars like Sarah need to take their climate research to the next level, including educational technology and tools, field trips, internships, curriculum development and career services. It also supports aspects of Duke that bring our community closer to nature, such as the Duke Forest and the cutting-edge Duke Marine Lab in Beaufort, North Carolina.

Since connecting with Pilkey, Sarah’s work has turned to include North Carolina and the damages brought about by Hurricane Florence in 2018. By wrangling data from the National Hurricane Center and elsewhere, Sarah wants to uncover social vulnerabilities in the population where the threat of storm surge remains.

“We are radically changing the earth’s systems,” Sarah says, “so the world needs more people with radical dreams of changing our world.”

Soon, Sarah will co-author a paper with Orrin Pilkey, completing her radical dream.